In the previous post I covered the first 4 of 8 elements of media history that I’ve found useful for teaching. Here are two more.

If many very small publishers have survived into the twenty-first century (certainly helped by the internet and new digital printing technologies), nevertheless a distinguishing factor of the twentieth century, especially the latter part, concerns the concentration of ownership of the media. I’m thinking here of the sublime growth of international conglomerates and transnational book production in line with just about every other manufacturing industry.

Ever since Paul Hamlyn in the 1950s escaped the restrictions of paper-rationing still in force in Britain by having his books manufactured entirely in Eastern Europe, book production became increasingly international. Even in the long gone 1999, it was quite normal for an author to key in her work in London on a word processor, send it to a publisher whose office might have been in New York who sent it to be typeset in Hong Kong, printed and bound in Singapore, for distribution to an Anglophone but world-wide market. What once were comparatively small publishing houses of perhaps 50 or so staff which carried the name of their founding father whose descendants headed the business are now huge transnational and transpersonal conglomerates.

It was the 1980s, the era of “deregulated” mergers and acquisitions, that saw the virtual elimination of the “gentleman publishers” and the restructuring of the whole publishing industry. The restructuring was due not only to deregulation, however, but also and not least by how the contemporary decreased funding of education led to a correspondingly decreased (and less seasonally reliable) demand for textbooks and library books within the UK. The demand was not only smaller but less predictable. Then again, the appreciation of sterling against the currencies of countries to which Britain had been exporting in large numbers since the 1950s made exports expensive and difficult.

Macmillan’s is a good example of a firm that illustrates how the industry was restructured in the second half of the twentieth century.

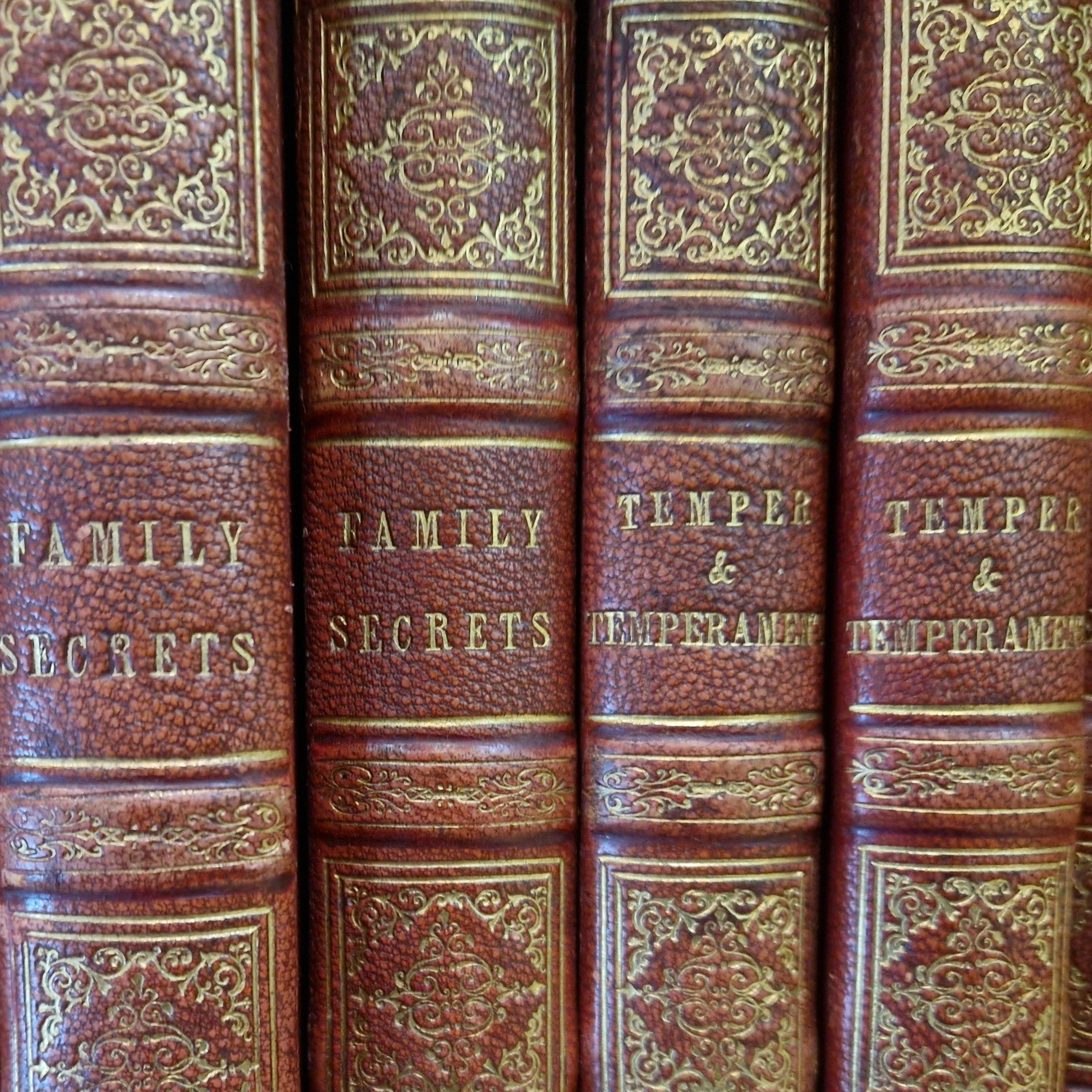

The brothers Alexander and Daniel Macmillan, originally from the Scottish island of Arran, had founded the company in 1843. They aimed mainly for a target audience with a large degree of cultural capital, publishing Charles Kingsley, Thomas Hughes, Lewis Carroll, Tennyson, Henry James, Thomas Hardy, Rudyard Kipling, H.G. Wells and so on. In the twentieth century Macmillan’s published Ouida (to whom they were very generous in her declining years), Yeats, Sean O’Casey, John Maynard Keynes, and many other well-known names. The talent-spotting talent of the Macmillan family, their canny awareness of the coincidence of cultural and financial capitals, were not confined to fiction and poetry: they also published periodicals and reference texts – Grove’s Dictionary of Music was theirs, for instance. The firm increased in size and influence throughout the nineteenth century and most of the twentieth, reaching its apogee in Conservative politician, Harold Macmillan. After having served as Prime Minister between 1957 and 1963, he withdrew from politics and took on (as Macmillan’s website tells me), “a leadership role at the publisher. He instituted an ambitious program that led to international expansion. The Education Division grew significantly and standard reference works and scientific magazines were also added to the list.” (see Macmillan’s interesting inhouse timeline and also Elizabeth James’s Macmillan: A Publishing Tradition 1843-1970, 2002)

Although the family still has a substantial interest, Macmillan’s is now owned by the enormous German media company Verlagsgruppe Georg von Holtzbrink – which owns the German national Die Ziet, which its website tells me is “Germany’s largest opinion forming newspaper”. It also owns Germany’s equivalent of the London Evening Standard the Berlin Der Tagesspiegel, 5 different German fiction imprints, a Swiss fiction imprint and 2 New York based houses Henry Holt and no less than Farrar Straus and Giroux, 8 local newspapers in Germany, 2 companies that make documentaries for TV, shares in a large number of radio stations, and various subsidiaries that publish on the internet and on CD. Macmillan’s itself has numerous subsidiaries in 70 countries, the result of Harold Macmillan’s global expansion plans. Since 2000 it has run an academic imprint called Palgrave, the result of the merger of the US St Martin’s Press and the UK Macmillan’s.

An even larger conglomerate is Pearson’s. It owns Penguin, Longman and Simon and Schuster; it produced the late twentieth-century hugely successful TV series Baywatch, The Bill and Zena Warrior Princess; it owns the Financial Times, The Economist; it ran Thames TV, has a large stake in Channel 5 and is the world’s largest education publisher. It has for some decades now invested heavily in electronic media, especially the on-line provision of share prices.

There are many issues involved in the creation of these huge conglomerates with their stress on marketability and share prices. One revolves around the value of such industrialisation of knowledge. There was a vigorous resistance already in the nineteenth century: William Morris and the Pre-Raphaelites spring readily to mind. In the 1890s many small scale presses had been set up, but their energy and usually socialist and artisanal ideals had all collapsed by the early 1960s. Does this collapse indicate the dominance of books tailored by market researchers, the heartless triumph of the machine – and offer opportunities for paranoia about who controls the knowledge available to us?

While made-by-committee books based on detailed market research certainly are published, it’s a universal axiom in publishing textbooks and commentaries that the indefinable flair of individual editors and their relationship to individual authors is still key to publishing. As one late twentieth-century textbook on publishing explained, “Good personal contacts are paramount” (Giles Clark, Inside Book Publishing, Routledge 1994: 67 – the site associated with the book is very good). And then one thinks of the disaster that brought Dorling Kindersley to its knees with its manufactured Star Wars book: phantom menace the item indeed was. The company managed to sell only 3 million of the 13 million Star Wars books it had printed. This was the main contributing factor to the heavy losses it posted in May 2000 of £25 million. DK was bought out by Pearson’s who joined it to the Penguin Group.

Then, if we are fearful that such transnational conglomerates might control us like Big Brother, we have to reflect on the issue of how centrally controlled they actually are. I remember being told by an editor for Palgrave that although the von Holtzbrink family owns large numbers of shares in the conglomerate that bears their name, they’re only interested in seeing the balance sheets every 5 years or so. They dont interfere. Individual editors operate independently and are, rather, assessed at the local level on the overall profit distribution of the books they have commissioned. Power is diffuse and capable of many different variations, promoting many different tastes and value systems.

While there are certainly issues of control over what becomes available to us to read – the Assange case is proof of that (and see eg the debate over Canongate’s publication of his unauthorised biography in 2011) – few readers feel constrained by what is available except by price. Indeed, given the explosion of small independent publushers in the twenty-first century enabled largely by new technology, many voices can be heard. This brings me to my next point.

From the point of view of most British users of books, issues of ownership are less important than the format revolution of 1935. Indeed, for most book readers today the twentieth century really began that year. 1935 was the year that Allen Lane started the Penguin paperback. Taking advantage of the monotype printing I’ve mentioned in a previous post, a technology that had been commercially developed in the 1920s, Penguin changed the face of publishing for ever.

The idea of the paperback was by no means new – books stitched in paper covers date from the late seventeenth century; in nineteenth century France, most books were published in the form to allow for binding according to the consumer’s choice. What was new was the industrial scale on which paperbacks were produced and marketed.

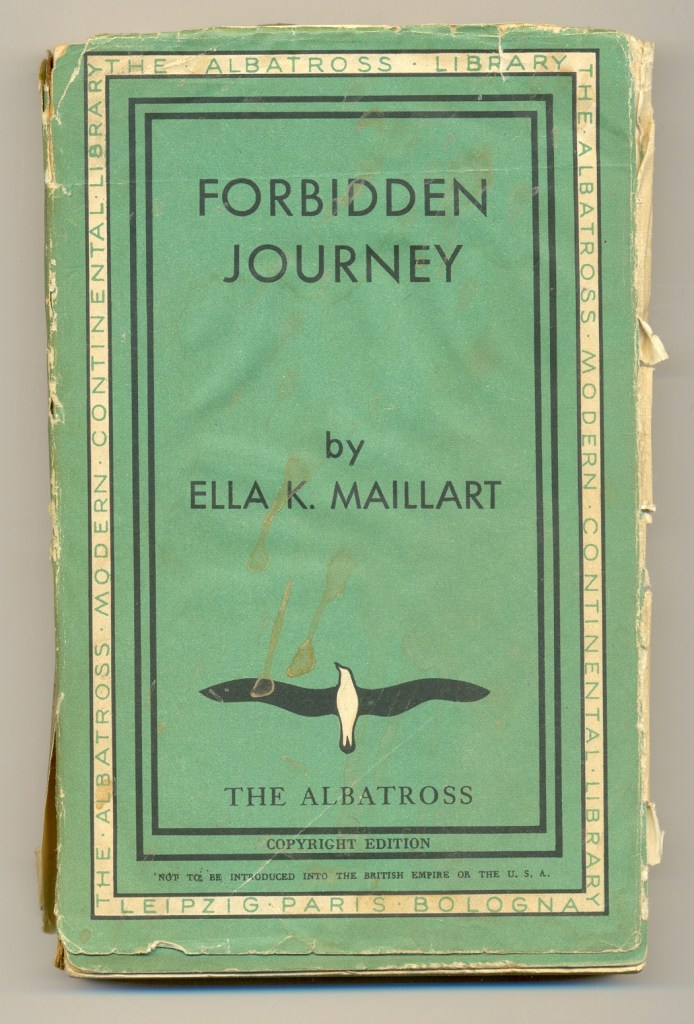

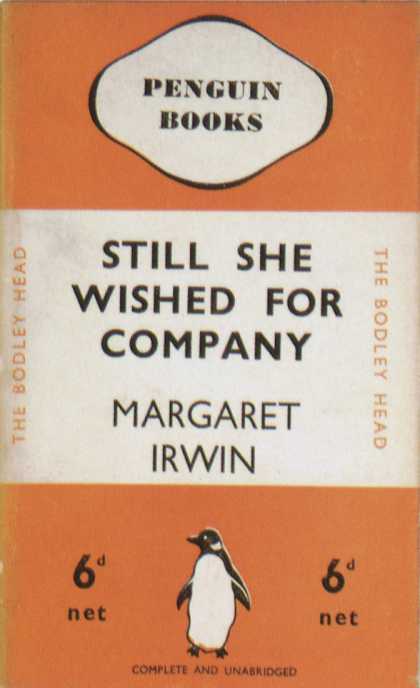

Penguin was born from necessity. Allen Lane was the owner of The Bodley Head Press, which he inherited from his uncle John Lane who had gained a reputation in the 1890s for the avant garde and “advanced” – Lane had published The Yellow Book, the showcase of aestheticism for instance. By the mid 1930s, however, The Bodley Head was in trouble financially: Penguin was a desperate attempt to save it. Allen Lane got the idea of the look for the series from Germany, where a paperback series called The Albatross had been started up by an Englishman named John Holroyd-Reece to rival the old-established firm of Tauchnitz who had been publishing paperback reprints for almost a century. Penguins were, however, by no means straight imitations of Albatross.

While early Penguins, like Albatross, were paperback reprints with visually distinctive covers of works originally published by other forms – as Phil Baines’s beautiful Penguin by Design: A Cover Story 1935-2005 shows us – Lane planned to sell Penguins very cheap: at 6d. Most revolutionary of all, he distributed them through outlets other than standard bookshops: the cheap department store Woolworth’s played a large role in the success of the Penguin imprint. Penguin’s real revolution lay not in its material identity as a cheap distinctive paperback but in establishing the book both literally and metaphorically in places in the market it had never before settled in. It paved the way for the supermarket books we know today.

For the next 20 years Penguin dominated the paperback market in the UK and helped normalise the format to such an extent that for most of us now the paperback IS the book.

What once was a technology meant for disposable reading, ephemeral in its structure, transitory in its nature, available for personalisation, came in the twentieth century to represent the quintessence of the book, the repository of (what we like to think of as) non-ephemeral knowledge.

We have now looked very briefly at 6 elements in media history, taking examples twentieth-century book history: here format and conglomeration, previously technology, ownership, regulation and distribution. What have we not discussed yet?

The fourth and last part of this series – on war and competing media forms – will be available here.

1 Comment