This historical definition of the twentieth century as related to book publishing over the last two posts have covered 6 elements: technology, ownership, regulation and distribution and conglomeration and the paperback format (the first post was an introduction). Before ending this consideration of the book in the twentieth century, I want to cover two more areas: first, the importance of war to publishing, and secondly, and inevitably, the relationship of book publishing to other media, a crucial characteristic of twentieth-century publishing.

We may not like to think this, but war is a time when information storage, retrieval and transmission of all sorts benefit from a lot of additional energy. We can see this in the effects of the Crimean and Peninsular wars in the nineteenth century on demand for newspapers, the effect of WWI on increasing demand for published images of the war and on staff shortages at printing works – which obviously caused its own problems – or what I’m going to write about here, the effect of WWII on the book as we know it.

In many ways, the second world war is just as important as any of the other factors outlined in previous posts.

First, WWII promoted the idea of a national literature which turn had a huge effect on the industry and on education. In America, for instance, it had an enormous impact on the consolidation of the canon of Great American Books. In 1941 was published one of the foundational books that came to define what was to be included in the American canon – and of course excluded from it. This was F.O. Matthiessen’s American Renaissance, a volume that set the syllabus for schools and universities for decades to come.

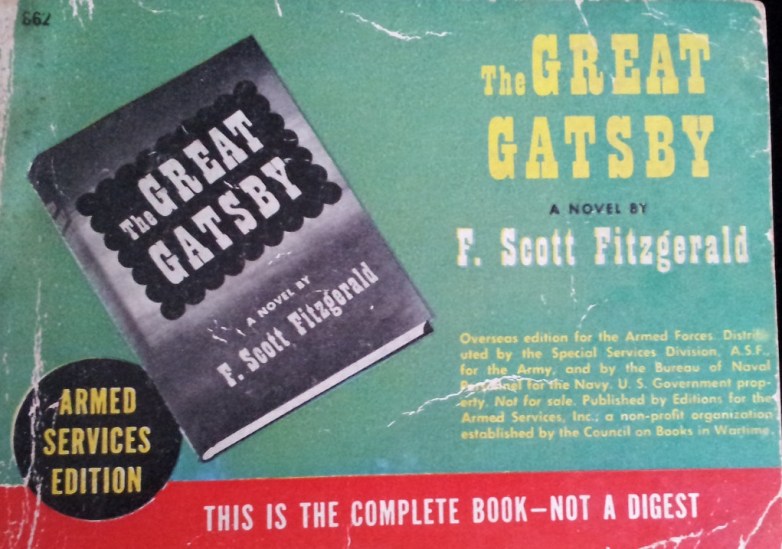

If this was what we may call a top-down effect, there was also some influence of what people were actually reading on what academics decided should be canonised: Fitzgerald’s Great Gatsby had sunk without trace, an utter flop on its appearance in 1925. Chosen for free distribution amongst the American forces during WWII partly because the copyright was very cheap, The Great Gatsby began to be read by large numbers of people for the first time. Following the war, academics who had read it when serving in the forces started to publish on The Great Gatsby and Fitzgerald in general.

More comforting – to me at least – than the idea of war encouraging an idea of a national literature, is the opposite: the idea of a world literature. It was a year after the war that Erich Auerbach’s magisterial Mimesis: Dargestellte Wirklichkeit in der abendländischen Literatur was published in Switzerland by Franke Verlag. Its research project was intended to show the cultural histories many of us share – a rebuttal of the divisions that the war between nations was using to justify itself. In its 1955 English translation the Auerbach became one of the founding texts of comparative literature, rightly praised (in my view) by Edward Said.

During the war there was enormous demand for reading matter: people not only wanted information on specific subjects such as the military – no fewer than 229 new titles were published on military matters in 1943 alone, as opposed to only 62 in 1937 – but military personnel had long empty periods of waiting between scenes of action while civilians had long evenings to kill with not much to do because of blackouts and rationing.

The publishing industry in Britain found that due to the rationing of paper it was unable to meet demand. Fortunately for publishers, it had a ready-made lobbying body in the Publishers Association which succeeded in preventing the imposition of Purchase Tax on books and in negotiating on a national scale the Book Production War Economy Agreement. This latter determined both the quality of paper and the size of type in order to produce savings.

Paper rationing – which came to an end only in 1949 – was instrumental in establishing the dominance of the paperback (which Penguin had already begun), for the production methods used for paperbacks used less paper than their equivalent in hardback. Furthermore, the pared down visual style imposed by wartime printing restrictions was highly influential on later developments in design.

These very brief paragraphs can only open the subject up for discussion rather than explore it in detail, but it is nonetheless important to acknowledge the very obvious fact that historical events, of which war is a very powerful example, impact enormously on the configuration of the book publishing industry. It’s a great area in which students can research individual items for projects.

One that strikes me is the surprising “Services Edition” (No. 481) of Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own that heads this post. As the back cover of the slim volume has it, these editions were “for circulation to the FIGHTING FORCES OF THE ALLIED NATIONS. THIS BOOK MUST NOT BE RESOLD.” By the time of its publication in 1945, Woolf had already committed suicide, though this is masked by a remark that she had “died” in 1941. The note on the author in the inner page defines her in national and canonical terms: “at the time of her death she had won a foremost place in English fiction, but she also ranks high among literary critics and essayists.” Readers need to read Woolf, suggests the note, because she is English and high quality according to sanctioned criteria, not because she has sold a lot (the original 1929 Hogarth Press edition had sold out very quickly as it happens). As with The Great Gatsby, in such framings we see an attempt to formulate the continuation of an illustrious national history, a promotion of “England” as a cultured, civilised and literary nation opposed to the barbarism of the enemy we see so prominent in British and Allied propaganda. This is, for all its endorsement of Woolfian feminism, the result of a carefully controlled (even while apparently librral) propaganda enterprise far removed from Auerbach’s call for unity.

The final element in my analysis of the “twentieth century” in publishing terms is relations between media. Books should never be separated out from other media: even the Gutenberg Bible was meant to recall manuscript rather than declaring itself to be entirely new. For most of the twentieth century we need to consider the relation of books to film, radio and TV – what I’m calling here “electric media” (as opposed to electronic) . I’ve no intention of going into the interaction of books with these media in any detail here, but there are a couple points to make that students find interesting.

Electric media have all interacted in complicated ways with literature: not only is there the obvious phenomenon of the spin-off, the film of the book, the talking book (on radio, tape or CD), the radio play of the book and so on, but also these other, electric, media have all affected literature itself. The influence of film is well documented, especially in the early twentieth century, from Kafka, Thomas Mann, Joyce to Fitzgerald (at the end of the century and at the obvious level of cultural reference, one recalls the importance of Rogers and Hammerstein’s The Sound of Music (1965) in Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things (1997)). Students have considered this in their projects and – even more commonly – how books (qua novels) have been adapted for the (cinematic) screen. This is all very familiar to us.

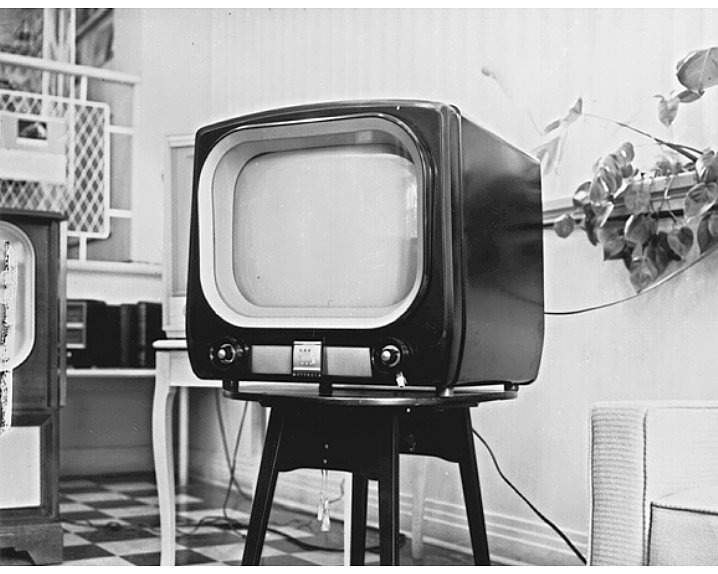

More importantly from my perspective, however, is the dating of the electric media’s influence on considerations of what “literature” is. While film had been widely consumed since the early years of the twentieth century, radio from the 1920s, from the 1950s it was TV that proved to be the competing – or perhaps complementary? – medium to the book. It’s important to remember how poor people were in the UK before WWII and before TV. Over the 1920s and 30s leisure accounted for less than 5% of national expenditure. Such poverty unsurprisingly hampered media expansion. It was the post-war boom that saw the greatest changes in media consumption – I’ve already mentioned the importance of the 1950s for the transformation of book production methods and in many ways nineteenth-century media production ended 50 or even 60 years after 1900, as the old production methods were replaced wholescale by the new only after WWII.

Consumed sitting in the home, TV became a rival not to radio (as is sometimes claimed) but to the book. The similar physical postures involved in the consumption of TV and the book put them into competition, while the radio could be listened to while involved in other leisure activities or while working. I still remember the BBC radio programme “Music While You Work” which had started during the WWII – in 1940. It ran until 1967. Asa Briggs’s 1970 The History of Broadcasting in the UK(Vol. III: 576–577 perceptively writes about how popular music was broadcast to aid productivity – this wasn’t a secret even to me as a child: it was just “normal.” But to watch TV you had to sit down and dedicate time to the small grainy screen in order to decode what the pictures meant. Today’s giant screens enable us to do the ironing while watching TV (or our phones enable us to watch while commuting). That wasn’t the case in the 1950s.

Now at exactly this time – the late 1950s and early 1960s – we see the birth of modern media studies, a birth largely and paradoxically in book form: not only Marshall McLuhan’s The Gutenberg Galaxy of 1962 and his Understanding Media of 2 years later, but work on the history of popular reading by Margaret Dalziel, Richard Altick, Louis James, Mary Noel and others. Richard Hoggart was considering The Uses of Literacy in 1957 just two years after ITV started in London and the BBC killed off Grace Archer in an attempt to prevent the curious tuning in to the upstart channel. Of course, there had been studies of mass or popular reading before – one thinks of Q.D. Leavis’s cantankerous and inaccurate (but very influential) Fiction and the Reading Public of 1932 ‑ but what was new at this time was the extent of interest in and concern over the new media and a corresponding re-evaluation of the old. No longer did “English” and “American Literature” remain with their sights on a few canonical classics, but the field began to widen to include texts not previously considered “literature.” Not only was contemporary popular culture analysed (Barthes’s journalism collected as Mythologies in 1957 remains a key example), but popular fiction and even journalism began to be studied historically. Important for me, this is the period when the Research Society for Victorian Periodicals was born, and when the interdisciplinary Victorian Studies was first published.

Television was not of course the only or even an obviously direct or major propellor of these paradigm shifts in the study of literature – the post-war expansion of higher education and the “reward” of higher education to working-class men who had been promoted to military officers are more direct causes, but the incursion of popular entertainment into the home, once the province of the book, certainly contributed to the gradual (and by no means inevitable or certain) democratisation and broader social study of literature and the transformation of Literature to literature I referred to in the first of this bog series.

What, we may well ask, will the electronic twenty-first century do to the book and to the concept of literature itself? Already there have been many studies and many predictions: which (if any) will become dominant?

When I wrote the first version of these past 4 blogs as a public lecture in 2000, I thought that perhaps we were entering a similar phase to the 1950s and 60s of new technology and new awareness: the world wide web was only 7 years old and everyone was excited about the possibilities for new configurations of meaning. A lot of writing appeared about that. 23 years on and the www has graduated and is thrilled less with new configurations of meaning than new possibilities for consumption. The paper book seems an antiquated medium from which targetted ads are excluded; many of us use electronic versions which offer different affordances. Yet the paper book continues to enjoy status amongst a certain social sector. Will that be sufficient reason for its survival?

1 Comment