My tenure as full-time Professor of English at the University of Greenwich ends today (31 August 2025). Inevitably, I find myself reflecting on what the institution and I have given each other. What follows is a development of a LinkedIn post in July, on the day I handed in the keys to my office.

The Necessary Distance from Distraction

There’s something about institutional life that can make you forget what you actually came to do: the endless small urgencies, the way certain personalities demand so much psychic space (and clock time), the tendency to measure yourself against metrics that don’t capture why the work matters. I spent more time than I’d like to remember caught up in dynamics that, in retrospect, were beside the point.

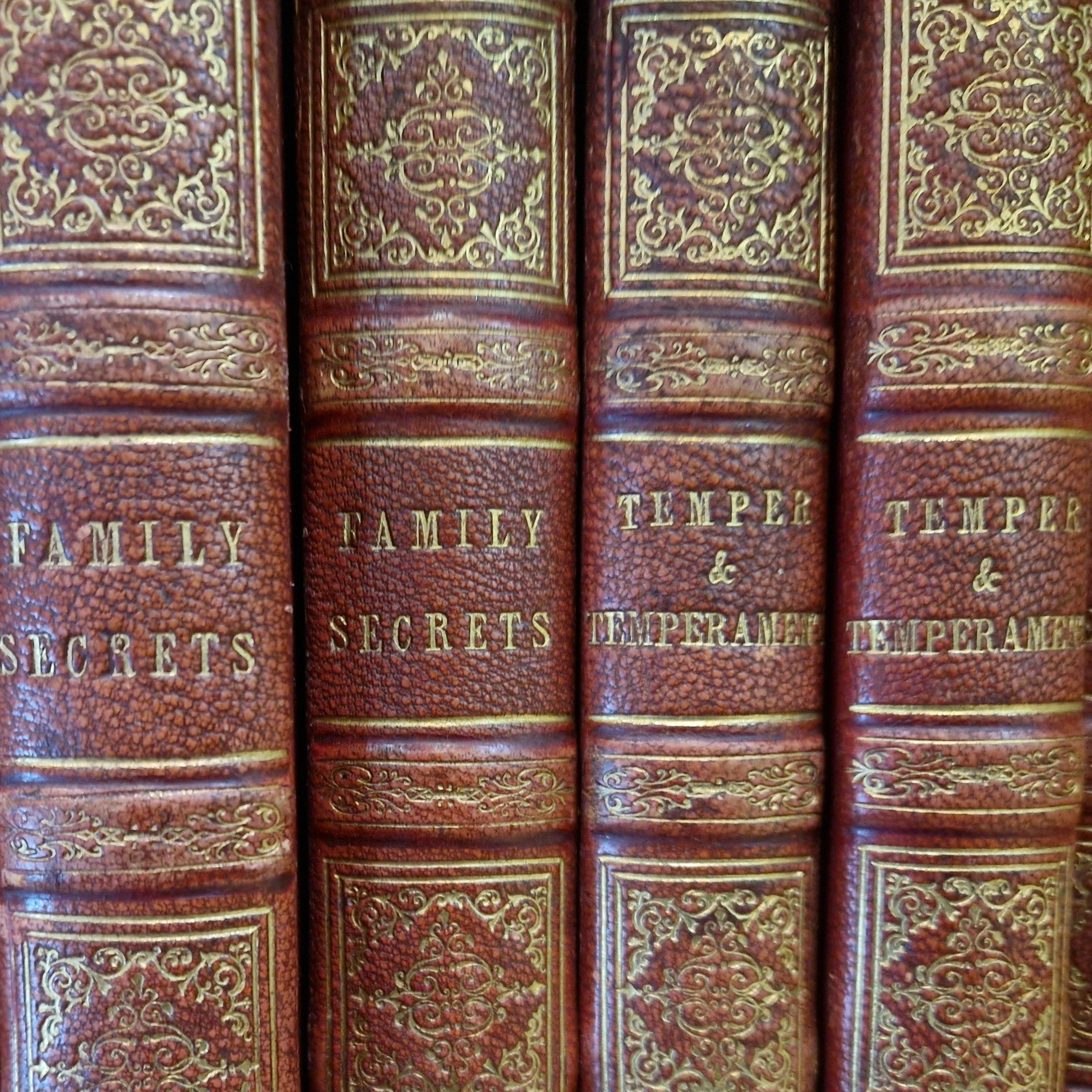

The sociologist Pierre Bourdieu’s concept of cultural fields illuminates this phenomenon. Academic institutions exist as contested spaces where symbolic capital is constantly negotiated through both overt competition and subtler forms of legitimation. My work on nineteenth-century periodicals has consistently revealed how media markets create similar dynamics of cultural positioning, where producers and consumers engage in complex strategies of distinction and accumulation between them and amongst themselves. The parallels between Victorian periodical production and contemporary academic practice become particularly stark when one experiences both as participant-observer.

But perhaps Bourdieu is not the only theoretical framework that need appertain. I have learnt a lot from thinking about non-capitalist economies, especially from Lewis Hyde’s reflections on “The Gift” and creative responses to the world, and from late Derrida. Indeed, I wonder if learning to notice where our attention is directed, and then to redirect it toward what actually nourishes us is a supplement or inadvertent gift that, if we have the energy and time for reflection, we can receive from corporate work under capitalism. Never interested in territory in ways that some hold close and fight with tooth and tongue and bloody nails for, at first I got upset and actively resisted. But gradually I learnt to become less reactive to those clashes of value that tear and scratch so painfully: competitive individualism versus collaborative community; fetishisation of impersonal quantification versus commitment to real human quality; abstract iron diktats versus the possibilities of vulnerable flesh; sometimes even individual rage and arrogance versus collective solutions – all manifestations of Bourdieusian competitiveness amongst perceived scarcity allied in its most extreme forms with less rational, even darker, factors and fears, shames and loves (for love isn’t always a good thing). The inadvertent gift is not indifference but distance.

Transforming Friction into Purpose

Reaction to such grating abrasion helped energise my determination to offer something new to the discipline and to sustain actively communities of ideas and practice whose people and ethos I genuinely believe in. The Victorian Popular Fiction Association (VPFA) exemplifies this commitment—a scholarly community that really does prioritise intellectual generosity over territorial defensiveness, collaborative inquiry over competitive accumulation, and welcome over exclusion, precisely in line with its commitment to questioning the violence of the canon and to broadening the syllabus.

These communities have always felt more pressing than any local and short-term territorial scratches. Through the VPFA presidency from 2019 to 2022, and through editorial work on Victorian Popular Fictions Journal, I have witnessed how scholarly communities can embody alternative values to those of extractive institutional cultures. The success of large international collaborative projects like the Routledge Handbook to Nineteenth-Century Periodicals and Newspapers (2016) and Researching the Nineteenth-Century Periodical Press: Case Studies (2017) or more recently Work and the Nineteenth-Century Periodical Press (2022) demonstrates – at least to me – that rigorous scholarship emerges from generosity rather than scarcity thinking.

What Work Has Given Me

What has work given me then?

The courage to commit to holding space for genuine collaboration and intellectual generosity; a renewed conviction that choosing to circulate rather than hoard energy, ideas, opportunities, joy, is not only its own reward but its investment; a clarified rather than just felt belief in the value of economic systems beyond and in addition to the extractive, quantitative and individually accumulative.

This conviction finds concrete expression in projects like BLT19, my digitisation initiative focused on nineteenth-century trade periodicals, to which PhD students, undergraduates and school pupils all contributed. Designed to demonstrate maximum social and academic value for minimal financial investment, and inspired in its conception by the Italian arte povera movement of the 1970s, it challenges the equation of monetary expenditure with scholarly worth. The project embodies a commitment to public access and pedagogical generosity, refusing to accept paywall restrictions as inevitable features of knowledge production.

And resilience, of course. As it turns out, resilience might be less about developing armour or invisibility and more about learning to distinguish signal from noise, turning away and tuning out so as to clear the space for creative joyful thinking without imposition but with clear and realistic acknowledgement of what we need to do to achieve what we really want. Again, not indifference but distance.

The Epistemological Stakes

This distinction between signal and noise carries methodological implications for humanities scholarship more broadly. My work at the intersection of literature, history, media studies and sociology has consistently emphasized unexpected areas of cultural exchange between popular and élite forms, across national and linguistic borders. Such interdisciplinary vision requires precisely the kind of attention management I have learned through institutional experience—the capacity to filter out disciplinary territoriality in favour of substantive intellectual engagement.

The challenge facing contemporary humanities research lies not in defending traditional boundaries but in developing new methods for understanding cultural transmission and transformation. Digital humanities methodologies, quantitative analysis, and data visualisation offer powerful tools for examining reception patterns and cultural circulation at scale. Yet these approaches remain underutilised in many corners of the academy, often due to the very institutional dynamics that privilege familiar over innovative methods, immediately profitable over speculative, the squeaky over the working wheel.

Beyond Extractive Models

It’s well known now that the contemporary university increasingly mirrors the extractive capitalism it ostensibly critiques. Faculty energy is harvested for administrative functions that do not seem to align with substantive educational or research goals. Scholarly labour is commodified through impact metrics that reduce intellectual complexity to quantifiable outputs and gamification. Student debt financing transforms education into a consumer transaction rather than a collaborative inquiry.

Yet within these constraints, alternative practices remain possible. My experience supervising five doctoral completions between 2020-2021, and my current set of six, demonstrates, I hope, how committed mentorship can embody non-extractive pedagogical relations. It’s not for me to claim this, but I hope each supervision relationship was and is based on intellectual generosity and conversation so as to prioritise student development over supervisor advancement, to create space for genuinely new thinking.

Methodological Implications

The experience of academic departure has clarified certain methodological commitments that have emerged from my research practice.

First, the importance of understanding cultural production as fundamentally collective rather than individualistic. My work 30 years ago on the London Journal revealed how seemingly individual authorial voices emerged from complex networks of editors, publishers, contributors, and readers. Contemporary academic authorship functions similarly, despite myths of solitary genius that persist in humanities culture. And today, that collaboration certainly includes AI which must, like all tools and collaborators, be treated respectfully yet critically.

Second, the necessity of attending to economic structures underlying cultural production. My chapter on periodical economics in the Routledge Handbook extended beyond publishers’ accounts to examine broader questions of cultural circulation and value creation, as does an as yet unpublished piece on the transnational economics of periodicals over the last two centuries. Such analysis is essential to my mind for understanding how knowledge production currently functions and how it might be transformed.

Third, the value of crossing geographical and linguistic boundaries in cultural analysis. My early experiences teaching in Italy, Romania and Poland, including leadership of the Crossing Cultures project that introduced gender, class, sexuality and ethnicity studies into Romanian secondary education (and which I’m still proud of for all its many faults – see here ), demonstrated how intellectual frameworks can translate across contexts while remaining attentive to and respectful of cultural specificity.

The Long View

Institutional departure offers a retrospective perspective unavailable during the urgency of daily academic life. Projects like the forthcoming Oxford Handbook to Victorian Popular Fictions represent collaborative achievements impossible within purely extractive models, and it is distance from such models that will more certainly enable its completion.

Such work requires sustained commitment to intellectual community over institutional advancement, to substantive inquiry over tactical positioning. It demands exactly the kind of attention management I have learned through institutional experience: the capacity to distinguish between genuine scholarly long-term priorities and temporary urgencies, between meaningful collaboration and performed collegiality.

The academy’s future depends on whether it can move beyond hasty, extractive models toward regenerative practices that nourish rather than deplete its participants. This transformation requires not just policy changes but fundamental shifts in how we understand scholarly value, institutional purpose, and intellectual community. It demands the courage to commit to genuine collaboration and intellectual generosity, qualities that institutional structures often discourage but which remain essential for meaningful educational and research practice. Above all, it needs the distance and careful attention to distinguish between a claim in a tick box and the realities of intellectual and social practice, and the affects and effects that dissonance and consonance between them can generate.

Gratitude itself functions as a form of intellectual practice. It requires sustained attention to what has been received rather than what has been withheld, to possibilities that have emerged rather than opportunities that have been foreclosed. Such attention, cultivated through the very institutional experiences that seemed to obstruct it, now becomes available for future scholarly and educational endeavours unconstrained by the particular dynamics of any single institutional context.

I really am grateful for what work has given me.