In the previous blog I promised to cover 8 routes through which print history and the twentieth century could be connected. Here are the first 4.

First print technology, that which enables literature to transit from author to reader.

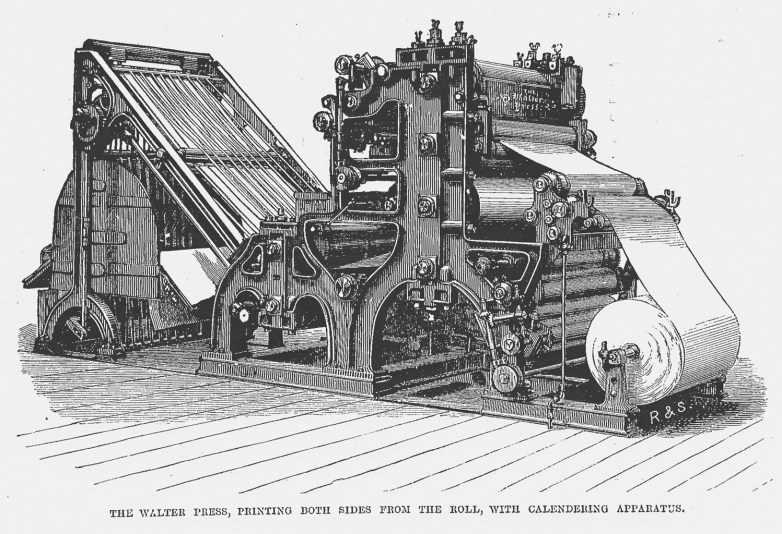

In the 1950s printing machines whose designs dated from the 1850s were still in general use. Yet paradoxically, printing technologies that in some ways are most characteristic of the twentieth century were first developed in the late nineteenth.

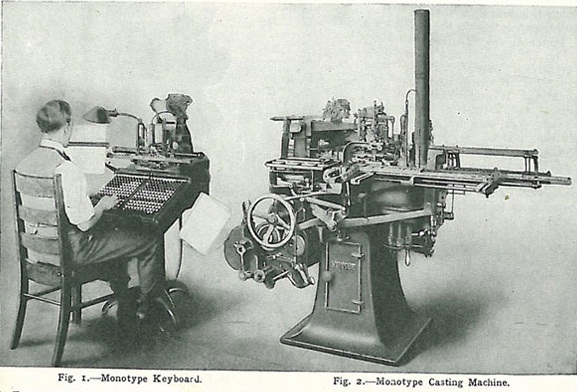

The two great revolutions in printing of the years between 1900 and 1950 were linotype and monotype. The Linotype machine was 1st installed on the New York Tribune in 1886; Monotype was invented 3 years later in 1889 but only commercially established in 1897.

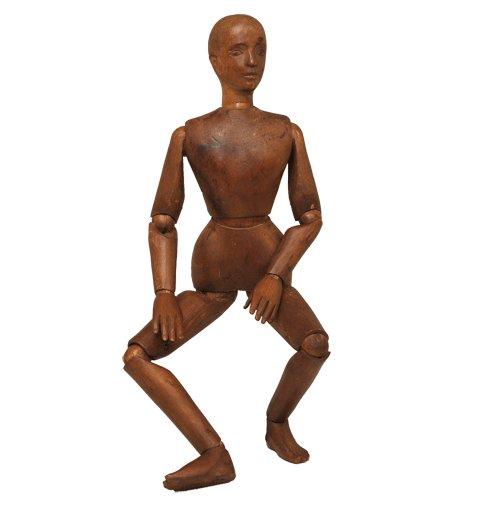

Perhaps you can see from the illustration how monotype employs a paper tape with holes in it as an intermediate storage and transmission technology between the keyboarding and typesetting. The idea derived from looms for weaving cloth interesting enough – the same technology that Charles Babbage used in his mechanical prototype of a computer. These technologies, esp. monotype, tripled the speed at which books could be produced and formed the basis for the revolution that was to happen in the 1930s with Penguin (on which see more later). But even more advanced technologies were invented in the late nineteenth century which were to be used commercially for books only from the 1950s. The 1890s saw patents for devices that set type photographically, but nothing came of them for almost 60 years with the introduction of the Intertype Fotosetter in the USA in 1945. This photographic technology in turn enabled the ever-faster production of books after WWII .

A second way twentieth-century publishing can be said to start in the late nineteenth is not purely technological but concerns conventions of literary property – who owns the text transmitted? I’m referring to the formulation of international copyright, most notably with the Berne Convention of 1885, through which a uniform international system of copyright was initiated. During the course of the twentieth century the convention underwent several modifications, including what is called the Rome revision of 1928 whereby the term of copyright for most types of works became the life of the author plus 50 years. This had in fact already been adopted in 1911 in Britain. In EU countries this has subsequently been modified to 70 years after the death of the author.

Copyright is incredibly important to the publishing industry: it is indeed its cornerstone on which its economics are based, but again with new technologies of the last 60 or so years – starting with photocopying which started to become common in the 1960s – it is undergoing a period of enormous stress. Perhaps in future times the twentieth century will be characterised as the period of efficient copyright – certainly more efficient than for any time before it, and perhaps after it too.

A third conventional continuity from the nineteenth century concerns censorship, particularly the persistence of the Obscene Publication Act. This dates from 1857 with a famous – or infamous – modification in 1868 that defined obscenity as that which exhibited a tendency to deprave and corrupt those whose minds are open to such immoral influences”. (Justice Cockburn in Regina v. Hicklin, a bookseller in Wolverhampton — see Victorian Print Media pp. 101-104 for extracts from this and other obscenity trials). Obviously, this had enormous impact on what could and could not be published in Britain. Lawrence’s open discussion of sex in The Rainbow in 1915 notoriously led to the seizure of 1,011 copies during a police raid on the London offices of the novel’s publisher Methuen. It was banned by Bow Street magistrates after the police solicitor told them that the obscenity in the book “was wrapped up in language which I suppose will be regarded in some quarters as artistic and intellectual effort”.

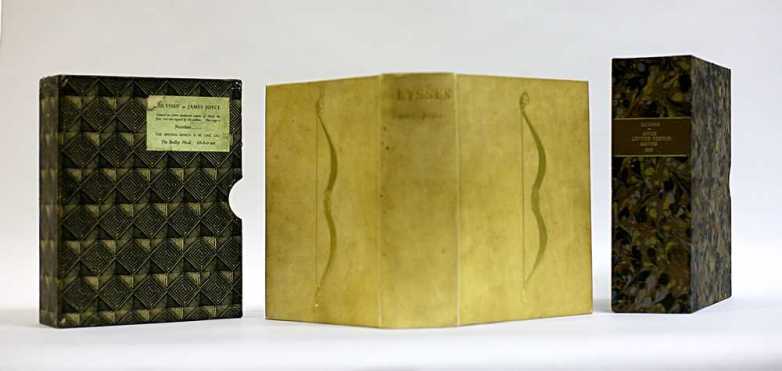

Then there’s Joyce’s Ulysses, published in Paris, which was seized by customs officers when it dared cross the channel into Britain (though curiously Bodley Head didn’t get prosecuted for publishing it in Britain in 1936). Radclyffe Hall’s Well of Loneliness had caused its publisher Jonathan Cape to be brought to court in 1928.

In 1959, there was a further and vital modification to the law of obscenity: now the work in question had to be taken “as a whole” and the interests of “science, literature, art of learning” could be adduced to defend a work from the charge of obscenity – “expert opinion” could be called. The following year the case of Regina v. Penguin Books over the publication of the unexpurgated Lady Chatterley’s Lover was a test case of this new law. Penguin won. Since then the question of obscenity has been continually debated, with concern in Britain at least has been far less over literature, however, than with film and video and, more recently again, the internet (see e.g. a recent article in The Guardian).

If then in three major respects twentieth-century publishing seems a continuation of nineteenth, in another it can be said to start perfectly on time on 1 January 1900 with the Net Book Agreement (NBA), signed by members of the then recently formed Publisher’s Association. The NBA concerns distribution. Again its roots go back to the nineteenth century — but it can also be regarded as a decided rupture with it.

The NBA was designed to prevent booksellers selling at suicidal discount yet price wars had erupted when in 1894 the lending libraries Mudie’s and W.H. Smith’s rebelled against taking three-volume novels. Publishers were forced to publish novels in one volume and more cheaply. This in turn meant that cheap books flooded the market and booksellers sought to undercut one another. Unsurprisingly, this spelled disaster for many booksellers (as well as publishers). Many booksellers went bankrupt. This in turn meant fewer outlets for the retail of books and the consequent risk of a decline in the market because of distribution problems – for if booksellers closed because they had been trying too hard to undercut their competitors how were publishers to get their wares to the consumer? Hence the need that some publishers felt to save booksellers from bankruptcy. The NBA was one solution. Through the NBA, the publisher allowed a trade discount to the bookseller only on condition that the book was sold to the public at not less than its “net published price” as fixed by the publisher. In Britain, a first attempt to introduce the net price principle by booksellers in the 1850s had been condemned to failure by supporters of Free Trade; but in the 1880s it had been successfully adopted in Germany. Encouraged by this toward the end of the century some British publishers, led by Alexander Macmillan, began to replace the variable discounts they gave to booksellers by fixed prices. To press for the new system, the Associated Booksellers of Great Britain and Ireland had been formed in 1895, and the Publishers Association was created in 1896. These two organizations then worked out the Net Book Agreement.

If the twentieth-century British book trade can be said to be the century of efficient copyright, it is just as much the century of the NBA – indeed it only collapsed in September 1995 through pressure from a complex of sources including rulings by the European courts about what constituted cartels and pressure from the Office of Fair Trading.

The industry itself had also changed though. The import of cheaper books from the US via Europe because of the strength of the pound, and not least the enormous growth of bookseller retail chains like Blackwell’s, Dillons, and Waterstones which by 1996 had grown to take over 30% of the U.K. market. These chains – in ever-reduced numbers amongst themselves – became the pacesetters in the new deregulated market that emerged in the 1980s. They were able to launch full-scale retail marketing of the sort that had previously only been seen in UK supermarkets, such as price promotions on certain brands (or imprints, in the case of books), loyalty cards and hence database marketing based on analysis of what specific kinds of customers were buying where and when. Regulation (“deregulation”) encouraged the consolidation of the chains: complaints to the office of Fair Trading by more than 600 small publishers that Waterstone’s was abusing its (dominant) position in the market by seeking greater discounts from publishers were dismissed. More recently again, of course, Amazon has increased its market share of literary distribution to previously undreamed of heights. Are monopoly, oligopoly and cartels the inevitable end of a deregulated market as we saw in the Hollywood film industry of the 1930s before the Paramount decrees, where the studios controlled distribution, exhibition and production?