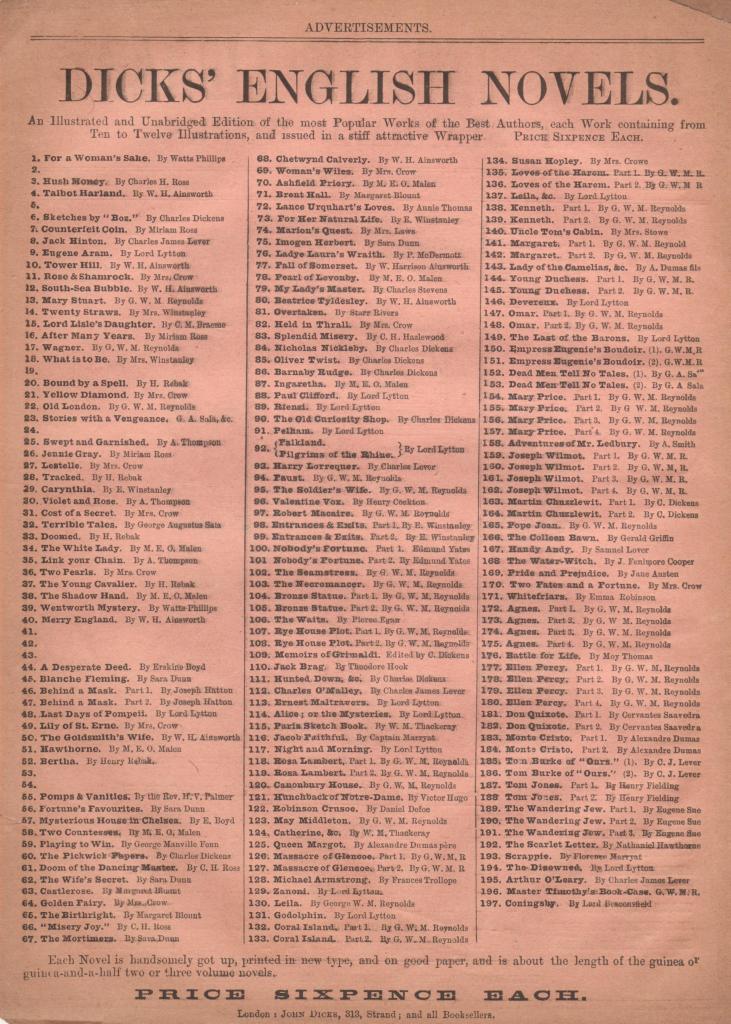

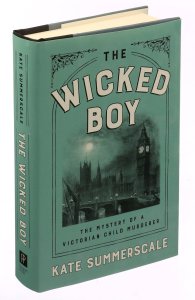

The moment (this is October 2024) when the “Queen of True Crime” , Kate Summerscale, has just published her 7th book, Peepshow, seems an appropriate one to revisit an earlier book of hers, The Wicked Boy: The Mystery of a Victorian Child Murderer (2016).

The Wicked Boy was very successful, garnering great reviews (here’s the Guardian‘s, for example) and winning the 2017 Mystery Writers of America Edgar award for Best Fact Crime. My students used to really like it when we taught it, especially as the murder occurred not too far away from Greenwich, across the river in Plaistow.

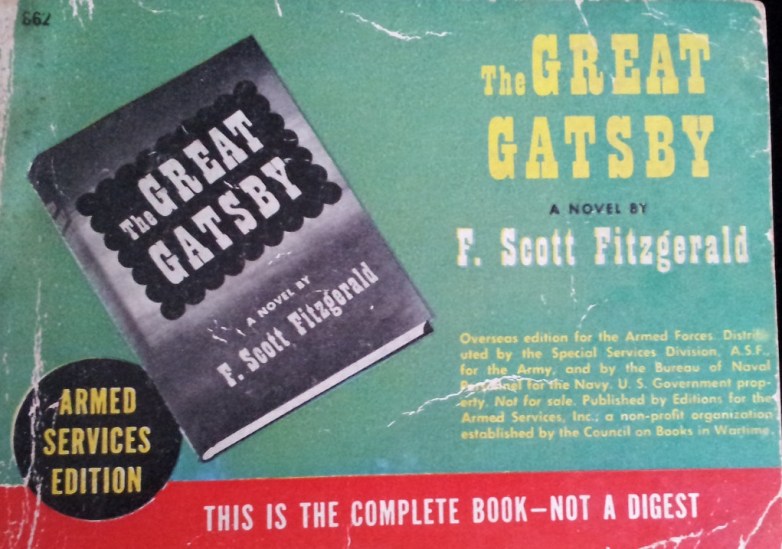

The book deals with an 1895 matricide by a 13-year-old boy, Robert Coombes, in the working-class East End of London, along with its context and its aftermath: the squalid city, the discovery and investigation of the crime, its coverage in the press, the possible effects of the boy’s sensational reading, his trial and imprisonment, his eventual release, service in World War I, emigration to Australia and his rescue and nurturing of a boy who was being abused.

It is easy to read as a story of redemption: the subtitle of the Italian translation even suggests it as a Dostoyevsky with a happy end: Il ragazzo cattivo ovvero Delitto, castigo e redenzione di Robert Coombes (“The Wicked Boy; or, crime, punishment and redemption of Robert Coombes”).

I have to say though that my take on the book was very different from the reviewers’ – much more theoretical for a start, and much more concerned with thinking about the emotional effects it had on us readers in the classroom. We read it in the light of crime fiction rather than “true crime,” for while we noted its very clear differences from fiction, we also noted a similarly powerful pull to read it, along with its development of characters and its forensic portrayal of context as a set of clues.

For a start, what does it mean that “Kate Summerscale” is the narrator of The Wicked Boy? Can we be sure that the “I” of the narrator (which emerges strongly only in the last part) is a simple reference to the author? Are we sure the narrator is not a constructed character? The fact that the narrator shares a name with the author might be confusing, but hardly unique, especially in postmodern detective fiction (at one point Paul Auster’s deranged detective-protagonist meets Paul Auster in The New York Trilogy). The “I” of the narrator seems very carefully constructed throughout, even when – especially when – it does not appear directly but simply as a collector of evidence or as a (sometimes vacillating) point of view. To me, it is as much a character as “Robert Coombes.”

I’m sure you’ll have noticed too if you’ve read The Wicked Boy that not only does the protagonist Robert Coombes change over the course of this “true crime” volume (it shares that kind of character development with the Bildungsroman) but the narrator does as well. Her investigations in the archives gradually lead her to discover unexpected secrets – that maybe Robert Coombs was more than just a “wicked boy” defined by the law and then “archived” – arrested, shut away in a lunatic asylum, forgotten. We gradually understand that “Kate Summerscale,” the character/ narrator, wants to get close to the subject of her investigations. She wants to understand him. By p. 197, she can surmise that “To survive the horror of the murder, Robert needed to forget. To recover from it, he would need to remember.” At the end, she even touches the hand of a man Robert helped survive abuse:

As I stood up to leave, Harry smiled and reached over to clasp my hand. He seemed glad to have told me what Robert had done for him. When I started work on this book, all that I had known about Robert Coombes was that he had stabbed his mother to death in the summer of 1895. It was astonishing to hold the hand of a man whom he had saved from harm. I still couldn’t be sure whether Harry knew about the murder. I hoped that he did, and had loved Robert anyway.

Wicked Boy, (pp. 196-7)

How can we understand this astonishing transformation from the coolness of the investigator we hear first, a narrator who seems to be on the side of forensic investigation and the upholding of due legal process, to the woman story-teller (yes, at the end the narrator is strongly gendered) who proposes a higher justice than the law can offer, a justice that gives us all a right to be loved, to be redeemed?

This doesn’t seem in the end to be a cool investigation of just the true “facts” of a crime: the narrator’s rooting in the archives seems to have changed her as well as her view of her central subject.

“Kate Summerscale” as forensic narrator concerned with weighing up the evidence uses a panoply of primary resources: newspapers and periodicals, books (often in rare or special collections – see for example note to p. 11 (p. 311) Archer Philip Crouch, Silvertown and Neighbourhood: A Retrospect (1900); a note to p. 253 [on p. 343] lists 3 rare book sources), manuscripts and paper documents in particular locations (E.g. “BRO (= Berkshire Record Office) D/H14/A2/1/1” – note to p. 222 [p. 337]; the diary of Charles Francis Laseron in Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales); secondary sources – the included bibliography is extensive and impressive (e.g. a note to p. 11, justifying descriptions of trams refers us to Jerry White, London in the Nineteenth Century: a Human Awful Wonder of God (2007)). The narrator later – when it becomes “I” – even records personal interactions – phonecalls, emails, casual encounters, interviews (see pp. 284-5, 303-7).

Archives are fundamental to Summerscale’s enterprise. But how do they lead to that tremendously affecting moment when she touches the hand that touched the hand… ? What might we mean by an “archive,” then, and what effects might that “archive” have on our understanding of the text and on the narrator’s relationship with the subject of her research?

Derridean Archives

Reflection on the nature of archives is hardly new. Twenty years ago, Marlene Manoff was able to write that “researchers [have been] proclaiming the centrality of the archive to both the scholarly enterprise and the existence of democratic society” (“Theories of the Archive from Across the Disciplines, Libraries and the Academy, Vol. 4, No. 1 (2004), pp. 9–25, p. 9) and even more has been written since then.

The turning point in archive studies is usually put at Derrida’s Mal d’archive [“archive sickness/ evil”], a lecture delivered at the Freud Museum in North London in 1994, and published first in French as Mal d’archive: Une impression Freudienne (Éditions Galilée, 1995) and in English the same year in the periodical Diacritics (Jacques Derrida, “Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression” translated by Eric Prenowitz, Diacritics, Vol. 25, No. 2 (Summer, 1995), 9-63).

Derrida had an audience of psychoanalysts and his lecture is very much addressed to them. Yet one of the many fascinating things about Derrida’s essay is how it has been treated by historians and critics. It’s as if they had read only the first few pages in which the archive is defined in historico-political terms. They forget that the lecture is actually about the nature and origin – the archives – of psychoanalysis composed for psychoanalysts in the symbolic “home” of psychoanalysis of the refugee Freud at a particular moment. Nonetheless, let’s follow the historians and literary historians, at least initially, and consider what they have taken from the lecture.

One of the commonest points that is made concerns how Derrida explains in his opening pages that – in his usual etymological and serious-fun play on words ‑ an “archive” was originally the building where the written laws of ancient Athens were stored. Only the magistrates of ancient Athens, the archons, were empowered to place them there, to put them in order and to interpret them.

In these introductory pages, the archive is always, according to Derrida, a place of “house arrest”, involving both the law and the idea of an enclosed place from which documents cannot be removed or put into general circulation: indeed, there’s a curious and all-encompassing, circular relationship of the archive and the law – the law proclaims who can access the archive which is itself the repository and authority behind the law. The “archive” is what gives the archons their power and enables them to keep it. It does that by keeping the laws secret. Only the archons can reveal those secrets, and it’s in revealing them – bringing the laws out from the archive and interpreting them – that they most clearly exercise their power.

In typically Derridean logic, without the idea of an archive, neither secrets nor laws could exist. The archive is the guarantor of the law by virtue of keeping it secret (of course Derrida is thinking of the Freudian unconscious and the Oedipal prohibition here). But then, as soon as an archon outs a secret or a law, it is ready to be archived and forgotten again, becoming again accessible only to a few. It’s just as if an archon (or, we might think, an artwork or therapist) were to show us a scroll on which laws are written only for it to be put back on its dusty shelf again, while we get on with our daily lives as before, having been entertained and distracted by the revelation (and perhaps a legal infringement or temporary escape of the unconscious) for a moment.

Following on from Derrida’s argument, it’s entirely logical that, if we think an equal-opportunities-for-all democracy is a good idea, we who are not archons with power will rebel – we will want to wrest the archons’ power from them. Power in such a democracy, we think, should circulate. Pursuing that logic further, all of us should want to be able to reveal secrets and show how the world “really” operates according to laws hidden from other people but not from us. Knowledge is power – we’ve been taught that since the beginning of school – and we want that power.

While for most of the time we just get on with life, there remains a nagging doubt – more acute for some of us than others – that the archons may give us only one version of ourselves and our history. They may say “you are a Wicked Boy” or “you are nothing but the murderer of your former employer” (Mary Braddon’s Henry Dunbar) or “you are a sexual experimenter and accidental suicide” (P.D. James’s Mark in An Unsuitable Job for a Woman) or a “serial bigamist” (Richard’s Marsh’s Judith Lee story “Matched”) or “a dangerous woman who can blackmail a king and thereby destabilise the whole social order” (the Sherlock Holmes story “A Scandal in Bohemia”).

But is that all there is to the identities of such characters – or of real people? Maybe we can prove that the archons don’t possess all the secrets as completely as they think, that we can observe and come to logical conclusions better than they. Maybe the Wicked Boy is more than that label. Even if we just want to assert ourselves and show the world that we are not simply as the archons describe us, we will want to show that we are, in short, better archons than the archons, or, this being a democracy, that we are at least as good as them.

We search for a trace that allows us to imagine we are rescuing secrets that the archive has hidden from the world.

Whole infrastructures have grown up according to that logic. Institutions like schools and universities aim to teach us to find things out for ourselves – or at the very least, teach us that there are secrets out there that we need to uncover. They tell us that we can become archons if we work hard enough. Such institutions operate doubly though: they both make a few of us feel like archons with the key to knowledge in our pockets or purses, but also they teach large numbers of us that we can never hope to understand the secrets of the archive. In the latter case, institutions teach us to be “the populace” – the ruled not the rulers, the powerless not the powerful.

Such thinking is what Derrida means when he writes that any “science of the archive must include the theory of [its] institutionalization, that is to say, at once of the law which begins by inscribing itself there [in the archive] and of the right which authorizes it.” (p. 4) Institutions like schools and universities are gateways to the archive: only a few of us are granted the right to pass inside where we can decode and profess the secret laws of the universe and of texts.

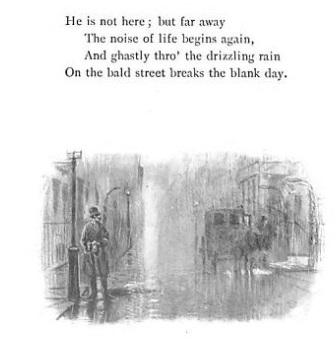

As we’ve understood by this point, the goal for those of us who root around in the archive is, according to Derrida, to find the previously secret. What that secret comprises is closely and inextricably bound up with two presuppositions: first, the idea that we are discovering a unique thing that only we know and, second, a powerful feeling – the magical, mystical moment of enlightenment we experience when we discover the secret, the authentic instant where we neither know nor care if we are the researcher or the researched, the ghost or the haunted, writer or written, archive or archon. We search for evidence where “the trace no longer distinguishes itself from its substrate,” as Derrida puts it on pp. 98-9 of Archive Fever – everything dissolves thrillingly into a feeling of oneness (very Lacanian psychoanalytic that). The past and present fuse, and in that moment death is overcome. To quote Tennyson’s “Break, Break, Break,” we seem to touch a “vanish’d hand” and hear “the sound of a voice that is still.”

Derrida’s way of conceiving the “archive” – at least at the beginning of his lecture – has not gone unchallenged, even though it has been very influential. Within standard historical and literary historical discourses, his proposal raises questions such as the following in Ed Fulsom’s excellent essay on “Archive” in the collection Literature Now: Key Terms and Methods for Literary History.

When we read Derrida on the archive, questions proliferate: how much of what we could think of as archives in fact exists outside of official archives and resides instead in garbage heaps or even in lost voices still travelling somewhere on sound waves? How much exists in the endless writings stored on tapes or records or disks or other outmoded technologies that are difficult if not impossible to access? How much of an archive is stored in the deep and inaccessible parts of any single human brain?

Ed Fulsom, “Archive” 23-35 in Sascha Bru, Ben De Bruyn and Michel Delville, Literature Now: Key Terms and Methods for Literary History( (Edinburgh Up, 2016), p. 23

Of course these are sensible questions within the discipline of history, including literary history, and they are central to postmodern writing that deals with the past. The garbage heap that Fulsom regards as a possible repository of secrets is not sealed from us as official archives are; the memories stored in the heads of our loved ones are, in theory at least, accessible to us. How can we claim therefore that these kinds of archive are ruled by the archons of knowledge? History, archaeology and literary history of the last seventy years has indeed raided both rubbish heaps and outmoded technologies as well as oral accounts by the living and the dead. Such sources are (again in theory) freely available to all.

There are two issues here though.

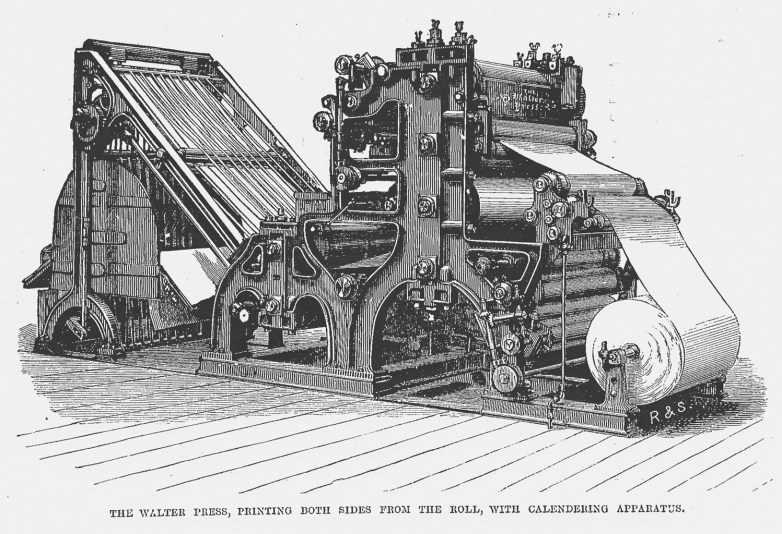

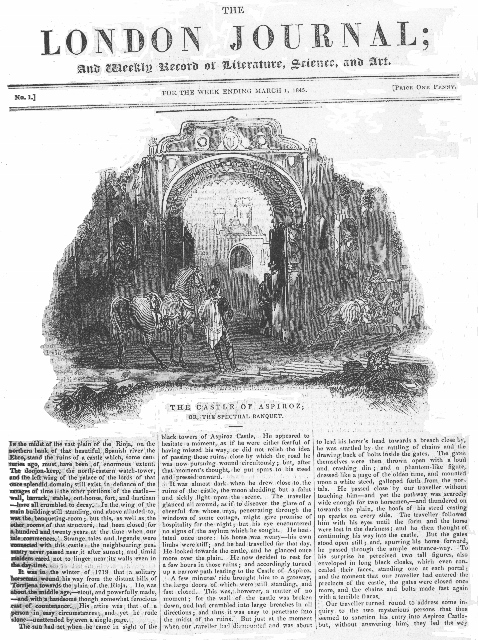

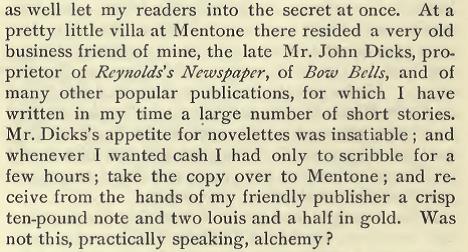

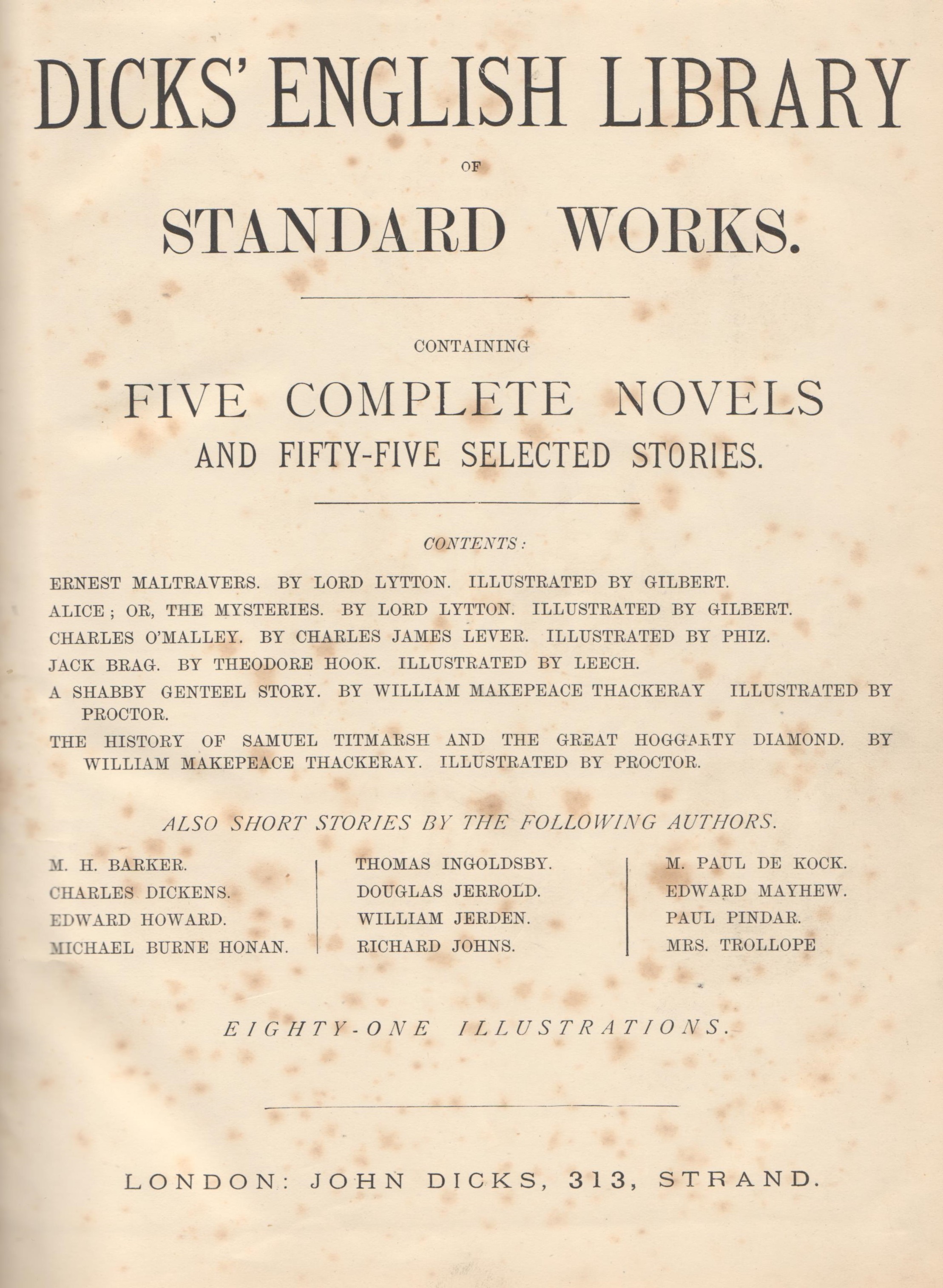

The first is that what is called “garbage” is determined by the powerful. We may not feel powerful when we throw the history of our drinking in the recycling bin, but we are much more powerful than the malnourished person who lights on our bottle in a rubbish dump in China. Texts once regarded as garbage because they didn’t conform to what was thought acceptable literature by the archons of culture may disappear altogether, recycled as note paper or toilet paper, leaving – at best – only the trace of their existence behind in catalogues (we recall how very few copies of the mass-market London Journal survive even thought it was read by 10-12 times more people than Dickens’s Household Words).

Secondly, to raid garbage heaps so that secrets are revealed requires skills – and what those skills are and who has them are determined by archons. So even if material may be freely available, to investigate it so that it yields its valid secrets requires access to the secret laws of the archons. And the loved ones whose own stories we’d like to hear may have understood that they are garbage according to the powerful and so may have deleted or altered them to accord with what they think is acceptable. How can we say in a simple way, then, that such stories are accessible?

(Perhaps indeed the archons, the archives and institutions are not just outside us. They are us. We have at least to negotiate with them to get our “I”s, our speaking selves, to speak at all)

The Forgotten Shelves of Derrida’s Archive: Psychoanalysis and Ethnic Boundaries

So far so good. That kind of institutional thinking is very useful for historians of all sorts. But what historians seems have elided and forgotten – “archived” to use Derrida’s terminology (or maybe “shelved” or, as I’ve done above and am.doing here, “bracketed”) – is that for Derrida psychoanalysis is at the heart of our concepts of the archive, and vice versa, for how we imagine an archive lies at the heart of psychoanalysis. And psychoanalysis is concerned to investigate our identities – who we are inside. It does not conventionally excavate the external power structures and processes that we are constrained and enabled by.

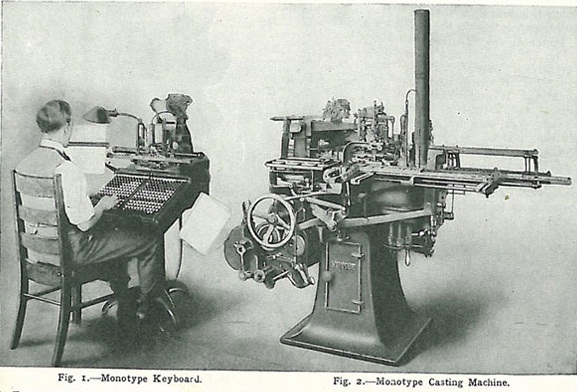

The “theory of psychoanalysis, then, becomes a theory of the archive and not only a theory of memory” writes Derrida at one point (p. 18), challenging a once dominant notion. And then he goes on to ponder the possibilities of an alternative history in which Freud uses a different technology which uses a different archiving mechanism – email, for example: how would psychoanalysis have been conceptualised if Freud had communicated with his friends and colleagues using email instead of pen and paper and the postal service? That too is a famous and oft-quoted point, and directs our attention to the “paratextual” and how technology affects our creation and understanding of texts (something I’ve written about quite a lot elswhere). But the point surely is that identities, in so far as they are an effect of archives, are both personal and institutional.

By far the greatest part of Derrida’s lecture – the part that historians neglect – is taken up with a thoughtful discussion of the claim by Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi in Freud’s Moses : Judaism Terminable and lnterminable (New Haven: Yale UP, 1991) that psychoanalysis is essentially Jewish. Derrida’s lecture is in reality a targetted intervention that needs to be read in its time and place, as a response to a Yarushslmi in the house of the refugee Freud, not as an ahistorical pronouncement.

Yerushalmi, writes Derrida, is the exemplary historian, exhibiting

the desire of an admirable historian who wants in sum to be the first archivist, the first to discover the archive, the archaeologist and perhaps the archon of the archive. The first archivist institutes the archive as it should be, that is to say, not only in exhibiting the document, but in establishing it. He reads it, interprets it, classes it.

Derrida, 1995, p. 38

And it is precisely this institutionalised “desire of an admirable historian,” not what has been left out of an archive on the rubbish dump of history or what technology is used to preserve it, that Derrida asks us to question. It is this “desire of an admirable historian” that is “archive fever”, the mal d’archive, the sickness/ evil in the title of his lecture. Desire is the foundation of the archive; the rational institution we see, the home of the Law and secrets, the Archive, is built on something quite other than the rational. And desire in turn is built on lack, on absence (we can’t desire something if we really believe we have it already).

In other words, we search the archive not really for rational knowledge of the secret or the law, but a feeling, an experience – a sensation that something is present when it can’t be. We root around in the dust because we want to encounter something or someone close up – in absolute closeness that fills the absence, the lack, beneath desire. We feel a void in everyday life, a distance from it – we are alienated from ourselves and from others, perhaps – and our investigations into the archive are a search for a way to bridge that gap, fill the void within ourselves, encounter the Other. This sensation generates a feeling of Truth, of access to what Lacanian psychoanalysis calls the Real. We want what Derrida calls elsewhere “presence”, the feeling that someone is right next to us, in communion with us. We know that such “presence” is just a metaphysical, impossible fantasy, but that doesn’t detract from its magnetic pull. This drive for such a sensation is what I tell my students is “the fiction of detection,” the fantasy that we have solved the mystery, revealed The Secret.

This psychoanalytic reading of the archive has little, it seems to do with the power relations around the archive that the historians are interested in. But Mal d’archive is a psychical drive – and it certainly doesn’t belong to any ethnic group. In fact it’s a universal human drive, claimed Derrida, rightin the home of the refugee Freud.

For Derrida has, it turns out, raised the question of the archive, its institutional violence and evanescent material technological basis, its sickness and fevers, to argue against Yerushalmi’s argument that psychoanalysis is the property of just one ethnic group, and not of the world. Yerushalmi, argues Derrida, is on the side of the archons and institutions who want to keep the secrets for one group. He is policing the archive for reasons he should reflect on.

Such a tactical move is perfectly in line with Derrida’s commitment to an ethics of hospitality that dislikes border controls and welcomes Others, including refugees like Freud (however problematic he saw that commitment – see Judith Still’s wonderful Derrida and Hospitality, EUP, 2012; and the two volumes of translations of Derrida’s 1995-96 seminars on Hospitality which came out in 2023 and 2024 from Chicago UP). It is also in line with his commitment to acknowledging the role of the irrational in what can seem simply rational, a commitment that itself is an inheritance from psychoanalysis.

Derrida is asking us – and Yerushalmi in particular – to use the insights of psychoanalysis to examine the foundations of our own stories – the discourses and institutions that govern what we do without our even realising it. In the house of Freud, he’s asking us to welcome truly Freudian thinking.

Archives and The Wicked Boy

So how does all this connect to The Wicked Boy? First of all, doesn’t “Kate Summerscale” (the narrator) set herself up as an archon of some incredible power? Goodness – all those archival sources! Just look at the notes! All those newspaper articles that she’s used to construct her story!

To impress us with her credentials as an archon in the orthodox institution of knowledge is surely the purpose of the notes and the bibliography. They are a sign that she must have worked for years over crumbling paper copies in dusty libraries and arcane archives. She’s got the skills and the knowledge so she’s closer to The Secret than we could ever be. She’s just like a private investigator at the top of her game, a Cordelia Grey or Margaret Wilmot or – since she narrates in the first person (so it turns out) – a Judith Lee.

Well, let’s dig a bit deeper and excavate “Kate Summerscale”’s own processes of generating secrets – let’s reflect on that character’s archival processes to reveal some secrets ourselves.

First thing, it’s clear to me (as a mini-archon in my own way) that her story is based mostly on online databases – especially the British Newspaper Archive (BNA). Rather than spend years in the paper archive, Summerscale has spent days in the digital archive, using keyword searches. You can do it easily enough yourself – just type for example “Robert Coombes” in the BNA and see what comes up. Other books she cites are freely available online through Google books or archive.org.

She hasn’t admitted any of this, though: her bibliography doesn’t list the BNA or Google books, only individual newspapers. Rather, Summerscale has mystified and glamourised her role as an archon to give us the impression that we are getting real value for money – that we are buying a huge amount of her labour. Of course the author has worked really hard – just not in the way that the creation of “Kate Summerscale” the narrator suggests. This isn’t deception on her part, just a conventional veiling of process that accords with the dominant rules of the knowledge-producing institution: academics still tend to cite the paper versions of primary sources even if we’ve found them online. It’s an unspoken institutional rule that either you know (that proves you are an archon) or not (you’re “populace”).

Second, let’s look at the metamorphosis of “Kate Summerscale” the narrator/ investigator. At first the narrator starts off like a cool police reporter: the tone is reasonable and controlled, a careful and very detailed description of events and environments. We might note the extraordinary emphasis on smell, for example. These days, in our hygienic world, we are so used to things not smelling that this emphasis, noted by several reviewers, comes as something of a shock: the stink of the ship Spain – a mix of “animal flesh, urine and excrement” (p. 12) – the powerful smells of 1890s London – “sour urinous… musty caramel… rotting cow carcasses… simmering oranges and strawberries… boiling bones and offal… bird-droppings… rubber, caustic soda, sulphuric acid, telegraph wire, dyes, creosote, disinfectant, cables, explosives, poisons and varnish…” (p. 13).

Yet all this horror is presented in calm forensic detail, with even rhythms and elegantly composed sentences. We are not surprised when the body is discovered and dispassionately described as if in a police report (see especially p. 41). “Kate Summerscale” here is very much on the side of the law and the reasoned forensic use of the archive. We readers seem to be positioned at this point as the jury deciding the wickedness or otherwise of the murderer. Did he do it? Well, yes, probably. But we are also being asked to judge whether he did it because of his environment (of which the smells, and the brutality of others, are a pungent part) or whether because he is essentially wicked inside, evil in nature, worthy to be thrown with other rotten characters on the garbage heap of history. The very asking of the question, though, opens us – and, with more certainty, the narrator – to change: which side will the narrator and we plump for?

For “Kate Summerscale” does not stay the same – her relationships to the law and to the archive are not fixed throughout. As I suggested before, her investigations in the archive gradually lead her to discover unexpected secrets – that maybe Robert Coombs was more than just a “wicked boy” defined by the law and “archived” – arrested, shut away in a lunatic asylum, invisible, secreted. We gradually understand that the narrator has been caught up in her investigations. This suggests, then, that the book is a Bildungsroman not just of the object of research, Robert Coombes, but of “Kate Summerscale” herself. And it’s archive fever that provokes this change.

The Archive is not just evil or repressive, then, for it can also be an engine of transformation: the power of the mal d’archive is not confined to the “desire of an admirable historian” to make the world conform to himself, but can open the possibility to encounter the Other, an Other.

What she’s doing becomes really clear when we find that, because “Kate Summerscale” herself is shut out of the archive relating to the asylum, she keeps padding around its perimeter, treading textual ground that might offer a glimpse of Robert – the descriptions of Broadmoor where he was incarcerated, her hunt for photographs (are they all definitely of Robert Coombes?). We get closer again when she tracks him down to Australia and locates people who knew people who knew him.

We discover that, like the detective Cordelia in P. D. James’s An Unsuitable Job, she wants to get close to the object of her investigations, to understand him, to make him present to herself and to us. She wants to reach out across the void of time, hear his voice and touch his hand. She wants to raise the dead. In so doing she seeks to elide the binaries of past and present, perhaps too of fiction and fact, to touch a “vanish’d hand” and hear “the sound of a voice that is still,” to undo death even while knowing that that is impossible. It is utopian, fantastical, a resource of hope, a reason to change.

That impossible desire to get close is surely the secret of why we continue to read, why we are touched by the two conjoined stories of “Kate” and “Robert” that come together in the end. “Kate” may not be able to touch Robert’s hand, but she can touch the hand of a man who touched him, and she can hope that he feels the same way as she does about Robert. This is the metaphysics of presence in literary and historical action: we know such desire for presence is impossible, but we keep hoping nonetheless. That is a glory, and a tragedy, a source of grief and of pleasure, a hope and an acceptance of defeat.

Archives, then, may always be political, institutional, systemic, but they are also emotional and experiential. They may harbour secrets from the past and try to ensure closure and certainty, but the desire archives excite can also be a driver to the future and to change in politics, institutions, systems and the self. What the narrator of The Wicked Boy does is show the transformative effect of archive fever so that, in the end, we can welcome what before we feared.

We can, as “Kate Summerscale” models for us, visit the archive not only to become archons who erect and police boundaries, but to become, also, hospitable.