Ouida, “A Dog of Flanders” (1872)/ Nello e Patrasche (1880)

editions in English and Italian

English edition: A Dog of Flanders edited by Andrew King

Italian translation (large file – be patient): nello e patrasche trans T Cibeo Treves 1880

“A Dog of Flanders: a Story of Noel” was originally written as a Christmas tale for the American Lippincott’s Magazine, where it appeared in volume 9, January 1872, pp.79-98.

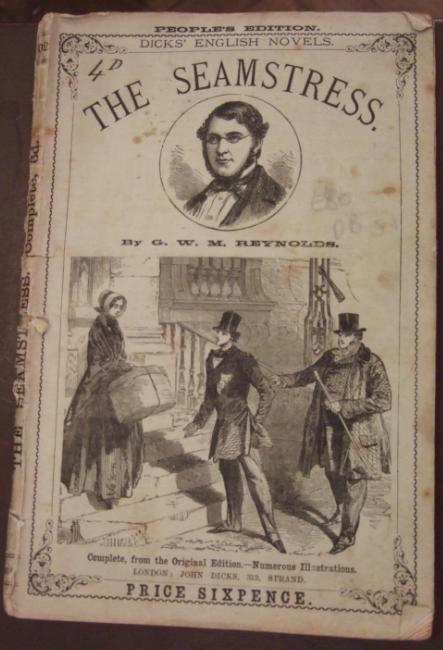

Later that year it was published in London, Philadelphia and (again in English) in Leipzig as part of a collection of short stories given various titles but which was (in textual terms) virtually the same: A Dog of Flanders and Other Stories (London: Chapman & Hall) with illustrations by Enrico Mazzanti; A Leaf in the Storm, and Other Stories (Philadelphia: Lippincott); A Leaf in the Storm; A Dog of Flanders; and other stories (Leipzig: Tauchnitz).

In 1873 there was a pirated Australian edition – and soon a flood of translations (some pirated and some not) in various languages. Beyond the usual French and German, there were also Russian, Polish, Finnish, and eventually Japanese, Korean and – surprisingly perhaps given its specifically Christian setting – Yiddish, as well as an enormous number of pirated American editions in English. There are at least 11 film and TV versions (the 1999 film can be found in its entirety here ) plus a documentary made in 2007 on the story’s incredible popularity still in Japan.

There was of course an Italian translation (called “Nello e Patrasche”). It came out in 1880 with the Milanese publisher Fratelli Treves, with whom Ouida published translations of several of her novels as well as collections of stories. “A Dog of Flanders” was, however, a makeweight in a volume whose principal part – and the only one mentioned on the title page – was Zola’s short novel / long short story “Nantas” (1878). Besides “Nantas” (pages 5- 177), the volume in fact also contained “Storia d’amor sincero” by Dickens (pages 181-196; actually an extract from chapter 17 of Pickwick Papers – the tale of Nathaniel Pipkin); “Nello e Patrasche” (pages 199-238); “Una Strage in Oriente” (pages 241-313) by the Russian journalist and traveller Lidia Paschkoff (or Lydia Pashkoff and other variant spellings in Roman script).

I’ve made an uncorrected PDF of Nello e Patrasche taken directly from this out of copyright edition. It is a very large file as it comprises images of the pages. It you missed it at the top of the page, here it is again: nello e patrasche trans T Cibeo Treves 1880

This translation is significantly different from the English not in its plot (though a significant name is changed) but in its lack of interest in sound and rhythm. Several descriptive passages are simplified it seems to me, which is strange as these were one of the key things Ouida was most appreciated for in Italy as elsewhere. This is how “Memini,” the translator of some of Ouida’s short stories as Affreschi ed altri racconti (Milano: Treves, 1888), described her powers of painting the Italian landscape in words:

I suoi paesaggi sono mirabili illustrazioni descrittive; alcune pagine… raggiungono la perfezione del genere e ci obbligano all dolorosa confessione della nostra inferiorità nello studio e nella descrizione letteraria del nostro paesaggio… (pp. xvi-xvii of the “Appunti critici”)

Why therefore did “T. Cibeo”, the translator of “A Dog of Flanders,” choose not to try to aim for similar effects in Italian? Why too is the title changed from a representative animal to the names of the two main characters? It’s a quite common title change in translations of this tale – try searching for “Nello e Patrasche” online – but we must ask what the implications of such a change might be.

And then there’s another curious thing. “Nello e Patrasche” was not reprinted in Italian so often as other Ouida stories. Her children’s story “La stufa di Norimberga” (“The Nurnberg Stove”) is very easy to find, for example, and has been translated several times, whereas the 1880 translation of “Nello e Patrasche,” buried in a volume whose main attraction was Zola and not even mentioned on the title page, was the only one I could locate really to exist (others turned out to be mistakes). Why was this story not so popular in Italy when it is so popular elsewhere? That is surely a question for investigation. It can’t be just the quality of the 1880 translation but something about the story itself. What values does it suggest that might prove unattractive to the Italian market? That is something that can and should be discussed in dialogue with Italian native speakers.

We’ll never know how many copies and translations of “A Dog of Flanders” were sold or how many people read this story. Certainly many millions in Japan alone beside the many millions in other languages. All we can say is that it was very successful amongst a very wide cross-section of society in many countries, including not only the general public but also amongst the elite. The artist Burne-Jones wrote a letter to a friend telling a lovely story of how he recalled (the influential Victorian art-critic) Ruskin and Cardinal Manning (Archbishop of Westminster and head of the Catholic Church in England from 1865 until his death in 1892) one day grubbing about on the floor desperate to find a copy of this story they both loved.

There are various free online editions of “A Dog of Flanders” available in English though none in Italian besides the one I’m offering you here. Some of the English texts are digital versions with little indication of what the source volume was, though you can find PDFs of actual books containing the texts through the very useful http://archive.org/details/texts site (see for example the beautiful – and certainly pirated – American Christmas gift-book version with lots of illustrations or the equally lavish 1909 Lippincott version illustrated by the famous children’s illustrator Louise M. Kirk).

The edition that I made is based on the Project Gutenberg text version, which claims to be a checked transcript of the 1909 edition from Lippincott.

I have, however, checked the Gutenberg edition against both the 1909 Lippincott version, the original serialisation and the first British edition by Chapman and Hall (no manuscript seems to have survived). I have edited so as to return the spelling to British standard (which Ouida always wrote in) and also adjusted the paragraphing again to the original (the Gutenberg text was in fact very faulty and didn’t even accord fully with the Lippincott edition, let alone the original).

If you missed the link at the top of the page, here it is again. It’s not a large file as it’s a PDF created from Word.